I watched my students, their faces stricken. My heart pinched for them . . . because I remembered how it felt, to learn some of these things for the first time.

This school year I’m teaching American Literature, and one of things I love about our school is the flexibility to somewhat develop my own curriculum. So I wanted to explore more than just the standard American Lit texts like The Red Badge of Courage and Grapes of Wrath, though we’re reading those too. I wanted to include some of the other American voices I’ve been learning to listen to over the past few years . . . voices often suppressed in our wider society, voices I hadn’t always realized even existed.

So for our second unit, I found a book of wonderful short stories by diverse Native American authors, from the late 19th to late 20th century. My students have loved the book, and we’ve had lots of good discussion. These young people continue to amaze me with their insight and depth. But since many of them had little to no context for Native American culture and issues before this—only one has had significant interaction with the Native peoples of this land at all, as her family is connected with the ANNA Call movement–I started by sharing a PowerPoint com piling a few of the things I’ve learned over the past several years . . . about some sides of American history that rather clash with our beloved ideas of the land of the free and home of the brave.

piling a few of the things I’ve learned over the past several years . . . about some sides of American history that rather clash with our beloved ideas of the land of the free and home of the brave.

We talked about the Doctrine of Discovery, where Pope Nicholas V basically gave carte blanche to all European Christians to take over any “heathen” lands they might happen upon, along with “all movable and immovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by [the native peoples] and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery.” (Papal Bull 1452)

We talked about former President John Quincy Adams, who in 1802 said of the First Nations of America, “What is the right of the huntsman to the forest of a thousand miles over which he has accidentally ranged in quest of prey? Shall the fields and vallies [sic], which a beneficent God has formed to teem with the life of innumerable multitudes, be condemned to everlasting barrenness?”

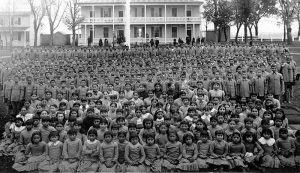

We talked about the Trail of Tears, the Navajo Long Walk, the Sand Creek Massacre of the Cheyenne in Colorado, the Wounded Knee Massacre of the Sioux that finally broke the last remaining Native resistance in 1890. We talked about the boarding schools, and “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.”

At one point, I paused for breath and glanced around at my students’ faces. Sometimes they can be a chatty group, but they sat silent, staring up at the pictures on the screen. And I saw it in their eyes—the pain, the shock. My heart panged for them, for I did remember how it felt.

This is America? This land they had been born in and loved, or, for our many international students, come to as a land of promise and opportunity?

Part of me rather ached to do this to them, especially when I read their responses after we watched Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee in class and I saw how troubled some of them were by this tragic true story.

But I think we need to learn these things. We need a common memory.

Mark Charles talks about how one of the huge deficits in America today, much of what drives our many viewpoint differences and racial tensions and misunderstandings, is our lack of a common memory. Native peoples remember the history of our country one way. African-Americans remember it another way. White people remember it in yet another—which tends to end up as the dominant narrative most often told.

But that doesn’t mean it’s the whole picture. Or a true one. And when better to start talking about it than Native American Heritage Month, starting today?

Because when our narratives don’t match, we end up clashing, misinterpreting each other, not listening to each other. Because we don’t understand how fundamentally our stories differ.

We don’t understand where our fellow Americans are coming from.

I felt awfully inadequate, in some ways, to try and educate my students on all this. I still have an awful lot to learn. So before I started, I shared pictures with them of my own teachers . . . and not just teachers, but friends.

Ted and Evie Charles. Their son Mark Charles and his family. Casey and Lora Church. The Stoner family. Richard Twiss, who though I’ve only heard him speak and read his book, still taught me so much.

Ted and Evie Charles. Their son Mark Charles and his family. Casey and Lora Church. The Stoner family. Richard Twiss, who though I’ve only heard him speak and read his book, still taught me so much.

They are the ones who have helped me see a more complete picture of America and its history and peoples . . . even if it’s been hard to hear sometimes. And they are the ones who, as they have embraced me, a white woman descended from those first “undocumented immigrants” of this land, have shown me that through listening to and reaching out to one another, even across centuries of past hurt and wrongs and current cultural divides, there can be—because of Jesus—bridges of love, and forgiveness, and understanding, and healing.

have helped me see a more complete picture of America and its history and peoples . . . even if it’s been hard to hear sometimes. And they are the ones who, as they have embraced me, a white woman descended from those first “undocumented immigrants” of this land, have shown me that through listening to and reaching out to one another, even across centuries of past hurt and wrongs and current cultural divides, there can be—because of Jesus—bridges of love, and forgiveness, and understanding, and healing.

That’s why we I think we need a common memory—so we can, by God’s grace, work towards truly becoming whole.

What do you think? Do you agree with the need for a common memory? Do you feel your own cultural heritage is represented in the typical American narrative? How can we work towards healing and understanding together? Please share your thoughts!

Save