It was a warm, blue-skied afternoon on our recent trip to Arizona and New Mexico, and Anthony and I were about to hike down into historic Canyon de Chelly. First Ted and Evie, our hosts and my dear friends for a number of years now, walked us to several of the most famous lookouts around the rim of the canyon.

I stood beside Ted and gazed down into this vast, red-rocked gorge in the earth, sacred to the Navajo for eons, then up at the towering spires of Spider Rock.

It was a little hard to take it all in, though, because of the group of tourists crowding next to us.

Mostly from Asia an d Europe, the tourists gathered around their guide, who was telling some version of the Spider Woman legend connected with Spider Rock. It didn’t sound quite right to me, but I’m no expert. I noticed Ted getting a bit antsy, though. After all, this is his canyon—his people, his stories.

d Europe, the tourists gathered around their guide, who was telling some version of the Spider Woman legend connected with Spider Rock. It didn’t sound quite right to me, but I’m no expert. I noticed Ted getting a bit antsy, though. After all, this is his canyon—his people, his stories.

Soon Ted attempted to engage some in the group, to tell them some of the real history of this canyon—how his people, the Diné, as the Navajo call themselves, lived and cultivated farms and orchards here for centuries. How in the 1860s, Kit Carson led the United States Army on a scorched-earth campaign designed to break this people once and for all. How they took refuge in this canyon but were eventually forced out to surrender, then marched over 400 miles, in winter, many of them to their death. Those who survived were imprisoned at Fort Sumner in eastern New Mexico for the next several years, where many more died. The Long Walk is the Navajo people’s holocaust.

But the tour guide didn’t want Ted taking over his tour, so he quickly hurried the group on. One man lingered to gaze at the vista, and Ted shared a little more with him. He smiled and listened a bit, then quickly moved on.

I stepped closer to Ted, now standing alone by the guardrail, looking over his canyon. It’s one of the few times I’ve seen his habitual cheerful calm disturbed.

“It kind of makes my blood boil,” he said…that people wouldn’t tell the true stories, and didn’t even want to hear.

My heart ached, and I felt a bit angry. Ted is my friend, my Navajo mentor, who with his Dutch wife have taken me under their wings and into their hearts, having me to stay with them multiple times, reading and correcting my manuscripts, teaching me Navajo history and culture to make my stories as truth-telling as possible, driving me and now Anthony all over the reservation, opening their hearts and lives to us. Ted is a former Marine, pastor, and high school teacher, a wise and loving husband, father, and grandfather. His parents went through the boarding school system, and his grandfather was taken on the Long Walk at only six years old.

His stories, and those of his people, deserve to be told, to be listened to. But all I could do right now was thank him for sharing his stories and his canyon, at least with us, though my words seemed rather inadequate.

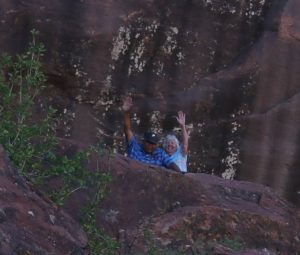

After a little while at another lookout, we followed Evie toward the start of the trail Anthony and I were to follow down into the canyon. We missed Ted, and looked back to see him still by the canyon’s rim, talking to another small group of visitors. This time, though, it looked like they might actually be listening.

“Let’s go on,” Evie said with a smile. “He’s found someone to tell his stories.”

In a few minutes, after we saw the tourists taking a photo with him, Ted caught up with us. But at least something of his smile was back on his face.

I hope those visitors took more away from their visit to Canyon de Chelly than just a brief anecdote from their trip…I hope something of the truth of this place’s history sank a bit deeper into their hearts. But at least they heard.

Anthony and I hiked down the canyon then, on the one trail open to visitors without a Navajo guide, while Ted and Evie stayed up top to rest and watch for us. The late afternoon shadows gave respite from the sun in the canyon, and a cool breeze teased our hair. At the bottom of the canyon, where several dozen Navajo families have taken up the tradition of living and farming once again, we found several brown-and-white horses—and a foal!—grazing in a grove of cottonwood trees. After snapping photos of the ancient ruins (predating even the Navajo) in the canyon walls, we visited with a Navajo lady selling jewelry made by her family and bought several delicate pieces for Christmas gifts.

Then it was time to go, hiking back up the shadowing canyon till we saw Ted and Evie waving at us from their perch near the top.

We stopped at Subway for dinner on the way back, as we were all hungry and tired. And while sharing two foot-long subs, we listened as Ted and Evie shared more of their hearts, their stories, with us. Some of it made my heart ache, as we heard of the still-present reality of discrimination against Native Americans, even in Christian institutions on the reservation…of how alone these precious friends of ours can feel…how rare it is, even among Christian friends, to find any genuine desire to understand how much the sins and wounds of the past still affect the First Nations communities of this land, and how we cannot move forward until we are willing to repent of and deal with our history.

We could do little else but listen. But I was grateful for my husband’s listening ears and compassionate heart, as well as his piece in this story, for part of Anthony’s own heritage is Native American.

I wished we could do more. But Evie thanked us later for listening, saying it meant a lot. And I was glad for something we could do, however small.

For maybe healing begins with listening, doesn’t it? Certainly in other relationships it does…I don’t think my husband and I have ever been able to make progress in a conflict until we’ve reached the point of really listening to each other, listening to understand, not to defend ourselves or try to prove our own point.

So why do we think working towards racial reconciliation—or racial conciliation, as Mark Charles, son of these dear friends, puts it—would be any different?

I have much to learn still, but I want to listen to my friends, listen “to understand, and not just empathize,” as Jevon Washington writes in this article here. And not be a “tourist” who sticks to my own more comfortable view of history and just walks away.

What do you think? Why is listening so important to any relationship? How have you seen listening help move toward reconciliation, whether interpersonally or racially? I’d love to hear your thoughts!

Kirsti, you write with such clarity and passion….

Thank you, Claudia–and thanks for stopping by and sharing! You are a blessing. 🙂

Kiersti, I listen when I read your stories. I cringe when I hear what the white Americans did to the Native Americans. But what good does that do? It doesn’t erase what happened, and I feel powerless to help. I grew up learning that Andrew Jackson was a great man. Then as an adult I learned how he not only turned his back on former Native American allies, he didn’t keep his word to them and was largely responsible for the Trail of Tears and the displacement of Native Americans in the southeast. It’s a shame and an embarrassment to me, and all I can do is ask you to tell your friends how sorry I am that it happened.

Marilyn, I so relate to that powerless feeling…and to finding our former heroes of history tarnished, if not outright villains. I guess one thing that struck me on this trip, and that was on my heart in writing this post, is that just listening IS doing something. Especially because it has been done so little. At least it is a place to start. Thank you for how you do listen, dear friend, and for your compassionate heart. Love you!